School of Fine & Applied Arts, Bangkok University

Dr. Pathitta Nirunpornputta

Abstract :

This project examines the fear of uncertainty, particularly regarding the future and the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on employment. It asks: “Why do people fear that AI might replace most jobs in the future?” As AI evolves, it serves both as a tool for efficiency and a source of anxiety, challenging traditional skills and raising concerns about human redundancy.

The research takes a practice-based approach, combined with autoethnography, reflecting on personal experiences throughout the project. In an era of rapid technological change, the study explores AI’s growing role in creative fields and the tension between innovation and adaptation. The researcher engaged with the collage, a resurging technique popularised through social media (TikTok and Instagram, 2024–2025) within the ‘junk journal’ trend (making scrapbooks), to examine shifts from handmade to digital design using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator. Additionally, digital printing was explored as part of the ongoing transition from handmade screen printing to digital methods, highlighting how traditional and digital techniques coexist.

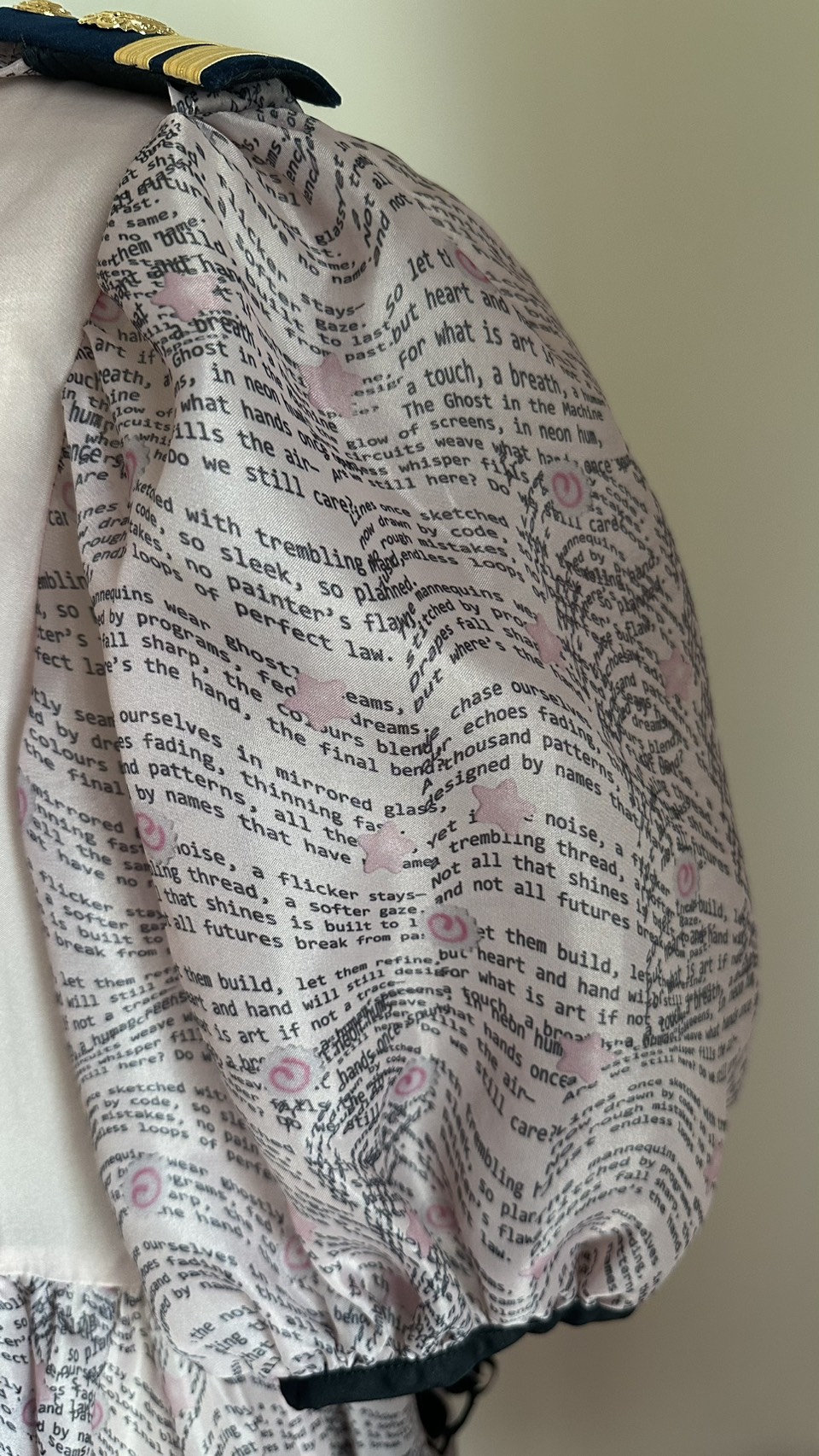

Beyond textile pattern design, the researcher collaborated with a dressmaker to create a dress inspired by educators’ uniforms, reflecting debates on AI’s role in education. This process highlights that while AI can aid design, the physical construction of garments remains reliant on human craftsmanship. The study also experiments with AI as a creative partner, investigating its ability to generate ideas, assist in design, and contribute to the making process. This approach provides insight into both human concerns about AI replacing skilled professionals and AI’s ‘perspective’ on these fears.

Ultimately, the project suggests that AI should be viewed as a ‘co-designer’ or ‘co-worker’ rather than a replacement for human creativity. Instead of making skilled professionals obsolete, AI offers an additional tool, an option rather than a threat, allowing designers to integrate technology into their practice. By positioning AI as a collaborator rather than a competitor, the research challenges assumptions about job displacement and explores how human creativity and technology can evolve together.

Objectives :

1. To explore the use of AI as a tool for garment and textile pattern design through practice-based experimentation. This objective focuses on integrating AI into the creative process, particularly in fashion design. Through a hands-on approach, the research investigates how AI-generated designs compare to handmade techniques and explores whether AI can enhance or hinder creative expression.

2. To investigate the concerns surrounding AI’s potential to replace jobs by examining its role in the creative process. By working directly with AI in the design process, the study seeks to understand its impact on creative decision-making. It questions whether AI serves as a replacement for human skill or if it acts as a co-creator that expands creative possibilities.

Conceptual Framework :

The study of the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in fashion design processes and its impact on job displacement is guided by two key concepts: AI as a creative tool and concerns regarding job replacement by AI. These concepts form the foundation for examining both the opportunities AI offers in creative fields and the anxieties it generates about the future of human expertise.

1. AI as a Creative Tool: This concept explores the increasing role of AI in creative industries, particularly in fashion design. AI is viewed not as a replacement for human creativity but as a tool that enhances the design process. The framework includes the use of AI in generating pattern designs, the creation of digital prints, and the integration of AI in collaborative design processes.

2. Concerns about Job Replacement by AI: The framework draws on discussions of job displacement, especially in education, where AI’s influence is being increasingly debated. The study examines this fear by comparing the transition from handmade craftsmanship to digital design and investigates whether AI can complement human creativity or lead to redundancy in certain roles.

3. The Tension Between Innovation and Adaptation: The framework also recognises the tension between innovation (AI) and the need for human adaptation in evolving fields. This is reflected in the researcher’s exploration of both traditional methods (collage, screen printing) and digital techniques (Photoshop, digital printing). It shows how AI contributes to the creative process, while emphasising that human expertise remains essential in the final stages of creation.

Process / Methodology :

1. Literature Review: The project began with an extensive review of related literature, particularly focusing on the transition from analogue to digital tools, and AI. This included an exploration of the value of handmade work and the rise of trends that promote the return to traditional methods, such as the ‘junk journal’ movement. These insights formed the foundation for the research and inspired the project’s creative direction.

2. Methodological Approach: The research adopts a practice-based approach, with an autoethnographic perspective. This approach allowed me to reflect on my personal experiences and thoughts throughout the creative process, particularly regarding the use of AI in design. It also provided a framework for observing how AI influences my work, as well as how I navigated the balance between tradition and technology.

3. Experimenting with AI: One significant aspect of the project involved engaging with AI tools, specifically ChatGPT, to explore the question: “Why do people fear AI might replace most jobs in the future?” Through conversations with the AI, I was encouraged not to fear its presence, but rather to see it as a collaborator or ‘co-designer.’ Additionally, I asked AI to reflect on human fears about uncertainty and the future, leading to the creation of a poem that became a central inspiration for my design.

**The Ghost in the Machine**

In the glow of screens, in neon hum,

where circuits weave what hands once spun,

a restless whisper fills the air—

*Are we still here? Do we still care?*

Lines once sketched with trembling hand,

now drawn by code, so sleek, so planned.

No rough mistakes, no painter’s flaw,

just endless loops of perfect law.

The mannequins wear ghostly seams,

stitched by programs, fed by dreams.

Drapes fall sharp, the colours blend,

but where’s the hand, the final bend?…..

4. Collage and Pattern Design: I also explored traditional collage techniques as a response to digital methods, using physical objects from my workspace, scanning them, and incorporating digital imagery. This process was carried out using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator to create designs that merge handmade elements with digital precision.

Techniques and Materials :

1. Collage: As part of the creative process, I used collage as a key technique, blending physical materials with digital tools. The collage was created by combining physical objects, scanned and digitally altered using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator. This technique reflects the tension between traditional and digital methods, highlighting the role of human creativity in the digital age.

2. Digital Printing: Another critical technique was digital printing, which served as a modern counterpart to traditional screen printing. Digital printing allowed for more precise and versatile pattern-making, with the flexibility to experiment with complex designs while still maintaining a handmade aesthetic in the final output.

3. Dress Design and Materials: The design of the dress was inspired by educator uniforms, with a personal twist reflecting my style. I selected an organza-like fabric in brown, not only to represent the professional uniform of educators in Thailand but also because of its transparent quality, which evokes a ghostly aesthetic. The transparency symbolised my role as an educator and the haunting, ethereal quality of the fabric aligned with the theme of AI’s impact—an invisible yet present force. Lace from the CHANTASIA factory was incorporated to evoke a sense of unpredictability in the creative process, with the lace’s damaged texture symbolising the imperfect nature of handmade work.

4. Inspiration from AI: The poem created by AI served as a direct source of inspiration for the textile patterns and dress design. The imagery within the poem, such as “ghostly seams” and “endless loops,” provided a conceptual basis for the patterns. This reinforced the theme of human creativity versus AI-generated work, allowing me to experiment with new materials and techniques that merged both worlds.

Result / Conclusion :

Humans have always gone through transitions, such as the shift from the analog to the digital era between the 1990s and 2000s. Now, AI marks the next era we must face, following the digital age. This project explored the question, “Why do people fear AI might replace most jobs in the future?” The fear seems to come from the uncertainty about what might change and how quickly AI is moving forward.

Rather than replacing artists and designers, AI is more likely to become a powerful tool that can boost their creativity. Those who learn to work with AI—using it for ideation, efficiency, and innovation—will gain an edge in the industry. AI might shift roles around, but human creativity will always remain the driving force behind fashion, art, and design. Humans will also continue to play a key role in selecting what AI offers, making sure the final outcome aligns with human values.

In the end, instead of fearing AI, it is more realistic to see it as a co-worker. The future of creativity will depend on how we collaborate with AI, using it as a tool to enhance what we already do. This project has shown that AI can be part of the creative process, and the key to the future is embracing these changes rather than being afraid of them.

References :

Alcoff, L. (1991). The problem of speaking for others. Cultural Critique, 20, 5–32.

Aranda, A., Florin, U., Yamamoto, Y., Eriksson, Y., & Sandström, K. (2022). Co-designing with AI in sight. Proceedings of the Design Society, 2, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/pds.2022.11

Azaldin, M. (2025, January 27). How junk journalling became a mindful ritual for busy women. Harper’s Bazaar UK. https://www.harpersbazaar.com/uk/beauty/mind-body/a63521016/junk-journalling/

Baba, N. (2014). Digital imaging and design experimentation in textile printing education. The International Journal of Visual Design.

Barnard, M. (2002). Fashion as communication. Routledge.

Calvi, M. (2018). The art of memory collecting. Penguin Random House.

Collins, L. (2025, February 4). Curious about TikTok’s junk journal trend? These page ideas are artist-approved. CBC Arts. https://www.cbc.ca/arts/junk-journal-trend-page-ideas-from-collage-artists-1.7449291

Cramer, F. (2014). What is post-digital? APRJA, 3(1).

Delamont, S. (2009). The only honest thing: Autoethnography, reflexivity and small crises in fieldwork. Qualitative Research, 9(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794108097423

Dunleavy, D. (n.d.). From analog to digital: Technology’s influence on the history of photography.

Ellis, C., & Adams, T. E. (2014). Autoethnography: An overview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12(1), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-12.1.1589

Erickson, M. (2024, December 20). Junk journaling is the wellness activity you should take into the new year. Body & Soul. https://www.bodyandsoul.com.au/wellness/mental-wellbeing/junk-journaling-tiktok/news-story/e3b4af9662b03e3be3aeab030eeeb98d

Fackler, K. (2019). Of stereoscopes and Instagram: Materiality, affect, and the senses from analog to digital photography. Culture, 2019(4), 45. https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2019-0045

Gardner-McCune, C., Touretzky, D., Cox, B., Uchidiuno, J., Jimenez, Y., Bentley, B., Hanna, W., & Jones, A. (2023). Co-designing an AI curriculum with university researchers and middle school teachers. In Proceedings of the 54th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 2 (SIGCSE 2023) (p. 1306). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3545947.3576253

Giuliano, L. (2019). Design and craft: The practitioners’ view. In A. Mignosa & P. Kotipalli (Eds.), A cultural economics analysis of craft (pp. 245–256). Palgrave Macmillan.

Gooby, B. (2020). The development of methodologies for color printing in digital inkjet textile printing and the application of color knowledge in the Ways of Making project. Journal of Textile Design Research and Practice, 8(3), 358–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/20511787.2020.1827802

Jones, C. T. (2025, January 9). Can junk journaling be an answer to digital fatigue? Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/junk-journal-tiktok-craft-trend-1235226883/

Kaur, H. (2025, January 25). In a chronically online world, people are finding respite in ‘junk journaling.’ CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/01/25/us/junk-journaling-benefits-wellness-cec/index.html

McIlveen, P. (2008). Autoethnography as a method for reflexive research and practice in vocational psychology. Australian Journal of Career Development, 17(2), 13–20.

Nakatsu, R. (2022). Development of art fashion by integrating digital art and digital textile printing. Nicograph International (NicoInt).

Sanders, E., & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4, 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068

Şuteu, M. D., Rațiu, G. L., & Doble, L. (2018). The interconnection of the programs Adobe Illustrator® and Adobe Photoshop® and their applicability in the textile industry. University of Oradea, Faculty of Energy Engineering and Industrial Management, Department of Textiles, Leather and Industrial Management.

Taylor, B. (2004). Collage: The making of modern art. Thames & Hudson.

Thatcher, K. (2024, December 9). Thinking of picking up a new hobby? Why not try ‘junk journaling’? Russh Magazine. https://www.russh.com/junk-journal-trend/